I came across this article while searching for information about La Mariecomo and witchcraft in New Brunswick. I have translated it with a PDF translator, which is less than perfect. The original in French can be found at the link below.

I will apologize for some of the language: terms like “taoueille”, “sauvage”, etc.

Canadian academics appear to be unencumbered by any form of cultural sensitivity. :/

https://www.erudit.org/fr/revues/rabaska/2009-v7-rabaska3475/038337ar

The Image of the Micmacs as Foreigners and Sorcerers in Acadian and Newfoundland Legend

RONALD LABELLE

University of Moncton

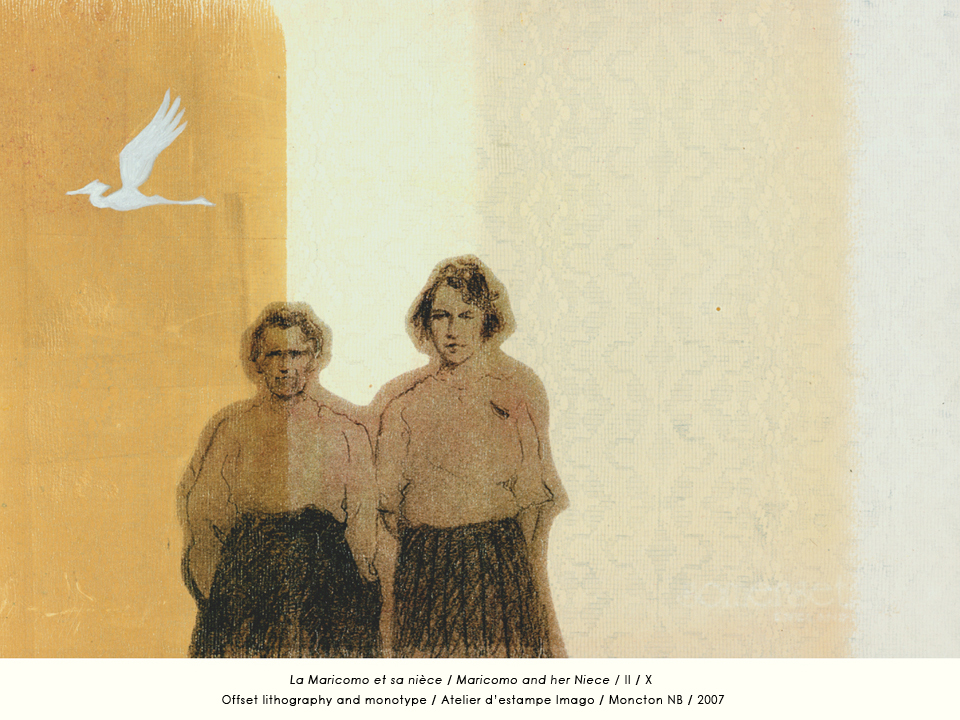

Witchcraft remains a little-known phenomenon in the cultural history of Eastern Canada, although it has been present everywhere since the beginning of colonization in the 17th century. In the introduction to her book on witchcraft in Newfoundland, Barbara Rieti points out that one could visit every heritage site in the province without finding a single reference to the existence of witchcraft . 1 Yet the Memorial University of Newfoundland Folklore and Language Archive is full of tales of witchcraft. Similarly, Nova Scotian folklorist Helen Creighton collected hundreds of tales in her home province, 2 while Sister Catherine Jolicœur did the same during her surveys of Acadians in New Brunswick, a province where one can visit at least one heritage site that documents witchcraft legends. The permanent ,exhibition at the Acadian Museum of the University of Moncton presents a painting illustrating the famous “Mariecomo” (see below).

In an article devoted to the vast collection of Acadian legends collected by Catherine

Jolicœur3 , I chose to illustrate the richnessof her collection by examining the supernatural stories built around the relationships between Amerindians and whites. The collection

includes approximately 400 legendary stories involving Amerindians. Of these, 350 deal with the power of Aboriginals to bewitch humans or animals, sometimes causing them serious harm. In most cases, contact between whites and Amerindians takes place when the latter stop in Acadian communities, either to sell baskets or other handicrafts, or to ask for charity.

- Barbara Rieti, MakingWitches,Montreal & Kingston, McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2008, p.

XIX.

- Helen Creighton, BluenoseMagic,Toronto, McGraw-Hill Ryerson, 1968.

- Ronald Labelle, “The Great Unfinished Work of Sister Catherine Jolicœur,” in Pauline Greenhill

and Diane Tye (eds.), Undisciplined Women: Tradition and Culture in Canada, Montreal & Kingston, McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1997, pp. 28-38.

Although stories tell of how the Micmacs came to the aid of the Acadians, for example by providing them with herbal remedies, the Aboriginals are generally seen as agents of witchcraft. An informant from Jolicœur expressed the distrust felt towards the Micmacs in this way: “A taoueille, when she has a little baby, when he starts to talk, the first prayer she taught him was the secret of witchcraft4 .”

Mary Douglas defined witchcraft as an antisocial psychic power exercised by people in unstable social situations . 5 As Barbara Rieti explains, projection plays a large role in the phenomenon: an individual with disturbing behaviour provokes negative feelings in members of a community, who then project their hostility onto him. The targeted person may be identified as a sorcerer or witch even before he has acted maliciously. Cases of interactions between Mi’kmaq and Newfoundlanders provide perfect examples of this phenomenon . 6 According to Douglas, witchcraft is most prevalent in small, well-defined communities, whose members have little mobility and little freedom of action . 7 In such societies, inevitable tensions are resolved by projection onto people perceived as outsiders or outsiders. This would explain the abundance of witchcraft legends on the coasts of Newfoundland . 8 The Acadian communities of the Maritimes share many of the same characteristics as those of Newfoundland, and it is therefore not surprising to find an abundance of tales of witchcraft there as well.

In a study of Native American witchcraft in Newfoundland, Peggy Martin suggests that the prejudices that existed in England against nomadic Gypsies may have been transferred to the Micmac people in Newfoundland .

Here again, the same parallel could be made with the Acadians whose ancestors would have brought with them prejudices about the Gypsies and other nomadic groups with whom they had been in contact in France. Whatever the origin of the belief, it is certain that the Micmacs were excellent scapegoats for those who sought to find those responsible for the wrongs they suffered. The Aboriginals were simply passing through and could not answer the accusations made against them.

- Anselme-Chiasson Acadian Studies Centre of the University of Moncton [now CÉACC], ethnology and folklore archives, Donat Arsenault collection, no. 12 (1976). The word “taoueille” refers to an Amerindian woman among the Acadians of southeastern New Brunswick.

- Mary Douglas, PurityandDanger:AnAnalysisofConceptsofPollutionandTaboo,London, Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1966, p. 102.

- Barbara Rieti, op.cit.,p. 43-44.

- Mary Douglas, op.cit.,p. 37.

- Peggy Martin, “Drop Dead: Witchcraft Images and Ambiguities in Newfoundland Society,”

Culture&Tradition,vol. 2, 1977, p. 37-38.

- Peggy Martin, quoted in Barbara Rieti, op.cit.,p. 52.

In order to better understand the phenomenon of occult powers attributed to Amerindians, it is useful to compare the stories collected from the Acadians, the English-speaking people of the Maritime provinces, and those of Newfoundland. The first question to consider is that of terminology. While in French, the term “sorcellerie” generally refers to anything related to evil occult powers, in English a distinction is made between sorcery, the act of casting spells or conducting magical rituals, and witchcraft,the innate power belonging to sorcerers and witches. 10

Acadian folklore does make a distinction between the two concepts, as “spellcasters” are generally referred to as individuals capable of performing sorcery , while an individual considered a true sorcerer, or witch, would be the equivalent of a witch in English folklore. The spellcaster possesses magical powers that allow him to bewitch humans or animals, but can still lead a normal life as a member of a community. He may be the general merchant, the village blacksmith, or a domestic worker. He is distrusted, but not necessarily completely excluded from local society. Sometimes a spellcaster decides to reject evil forces and then live in accordance with Christian morality.

The sorcerer or witch, by contrast, is considered the representative of the devil on earth. He is an individual who has sold his soul to the devil and is therefore damned. One tries to avoid any contact with him. Sorcerers or witches are relatively rare in Acadian folklore, although they have remained very present in oral tradition in some places.

Spellcasters, for their part, are attested everywhere. To take the example of the Micmacs, given that all Aboriginal people were believed to be capable of exercising magical powers thanks to their occult knowledge, they could all, in principle, be spellcasters. Among the Micmacs themselves, the buoin was an individual with supernatural powers, sometimes evil, who was close to the concept of the sorcerer in cultures of European origin. 11 The buoin was generally unknown to whites, given the superficial nature of the relationships that they had with the Amerindians. The Acadians therefore did not recognize that certain individuals who were members of the Micmac communities could possess supernatural powers exclusively.

Since the beginning of the period of contact between the two groups, there has always been a tendency to associate the Amerindians with demonic power,

- See Richard P. Jenkins, “Witches and Fairies: Supernatural Aggression and Deviance Among the Irish Peasantry,” in Peter Narvaez (ed.), TheGoodPeople:NewFairyloreEssays,London & New York, Garland Publishing, 1991, p. . 302-335.

- Peggy Martin, op.cit.,p. 40-41.

since in the European worldview, all forces acting on earth necessarily came either from God or from the devil12.

In the English-speaking communities of colonial America, the shamanic practices observed among indigenous groups were therefore quickly associated with the action of the devil. 13 The situation was hardly better in New France, where in 1632 the superior of the Jesuits, Father Le Jeune, described his mission territory as being “the empire of Satan .” 14

Historians have recently discovered that the perception of Native Americans as allies of the devil played a role in the witchcraft trials in Massachusetts in 1692. The inhabitants of this colony lived in fear of the Wabanaki people who occupied the northern part of their territory. They believed that the witches of the colony went into the forest, the habitat of the Native people, to meet Satan. One of the dominant figures in the witch hunts, Cotton Mather, considered all Wabanakis to be devils. 15 The Micmacs, like the Wabanakis, are part of the great Algonquian family and they have had ambivalent relations with the Acadians, characterized by a mixture of distrust and cordiality.

Unlike the New Englanders, the Acadians were never very alarmed by the presence of Aboriginal people near their homes, but their fear of their Micmac neighbours is illustrated by the fact that following the capture of the colony by England, they more than once cited the danger of attack by the “Savages” as a reason for their refusal to sign an oath of allegiance to the British crown.16

Despite their distrust of the Micmacs, the Acadians did not go so far as to associate them with demonic forces because most of them had converted to Catholicism very early on. This may explain why there was never a climate of panic surrounding witchcraft in colonial Acadia. The only witchcraft trial in the colony took place in 1685 and ended in a dismissal.

In her study of this trial, Myriam Marsaud explains that the accused, a man named Jean Campagna, was originally from the south of France and had first settled in Port-Royal, before moving to Beaubassin, a relatively closed community, where he had no family ties and where malicious rumours about him had spread.

- Robin Briggs, WitchesandNeighbors:TheSocialandCulturalContextofEuropeanWitchcraft,

Oxford, Blackwell, 2002 (second edition), p. 2.

- Mary Beth Norton, IntheDevil’sSnare:TheSalemWitchcraftCrisisof1692,New York, Alfred

A. Knopf, p. 59.

- Maxwell-Stuart, PG, Witchcraft in Europe and the New World, 1400-1800, Basingstoke (Great Britain), Palgrave, 2001, p. 96.

- Mary Beth Norton, op.cit.,p. 81-136.

- NES Griffiths, From Migrant to Acadian, Montreal & Kingston, McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2005, p. 272, 413.

quickly led to various accusations. 17 Campagna’s trial was held in Quebec City because of the complex legal procedures governing accusations of witchcraft at the time, which were supposedly instituted by the French authorities in order to put an end to the witch hunts that had been so numerous during the first half of the 17th century. 18 The first Acadian settlers had left France at the time of the witch hunts and they supposedly brought with them the prejudices and superstitions that had led to much disorder in the mother country. Jean Campagna, as a foreigner with questionable behaviour, threatened the stability of the Acadian community of Beaubassin, hence the title of Marsaud’s study, “The Disturbing Stranger.”

Oral accounts of events in Acadia in the 19th and early 20th centuries demonstrate that the same climate of distrust toward foreigners continued to exist. A well-known example dating back about a hundred years is that of Lazare Lizotte, from Chéticamp in Cape Breton. He was nicknamed “the Canadian” because he was originally from Quebec—in the Maritime provinces, Quebecers were formerly referred to as “Canadians” as opposed to Acadians. In his monograph on Chéticamp, Father Anselme Chiasson cites several oral accounts in which Lizotte casts spells or appears in the form of a large dog. 19 Many of the male sorcerers attested to in Acadian folklore were of either French or Quebec origin. Their status as foreigners therefore made them suspect.

In her study of Native American witchcraft as reflected in Anglo-Newfoundland folklore, Barbara Rieti concludes that racial stereotypes lead to a perception of “others” as dangerous outsiders.

She included in this category all those who had a lower social status than white men, including women in general and the Micmacs as a whole. It is easy to understand the perception of the Micmac as a foreigner who threatened the stability of local society, but it is more difficult to attribute this role to women. Richard P. Jenkins explains this in part by the fact that, in Irish society, women often changed communities at the time of marriage and therefore remained foreigners in their adopted village for a long time. 21 In a study of religious traditions in Acadia, Denise Lamontagne also makes the link between women and

- Myriam Marsaud, “The Disturbing Stranger: The Witchcraft Trial of Jean Campagna”, thesis (MA), University of Moncton, 1993.

- Robin Briggs, op. cit.,p. 290-291.

- Anselme Chiasson, Chéticamp –AcadianHistory andTraditions,Moncton, Éditions des aboiteaux, 1961,

p. 260-261.

- Barbara Rieti, “AboriginalÿAnglo Relations as Portrayed in the Folklore of Micmac “Witching” in Newfoundland”, Canadian Folklore Canadien, vol. 17, no. 1, 1995 p. 29.

- Richard P. Jenkins, op.cit.,p. 326.

witchcraft 22. After explaining how the Acadians and Micmacs share a devotion to Saint Anne as a protective grandmother, she writes:

Like the Western imagination linked to feminine power, which is symbolized by the dual image of the witch who casts spells and the midwife who heals, the figure of the Native American woman, as described in Acadian oral literature, illustrates in an exemplary manner this ambivalence of feelings expressed towards feminine power, both attractive and disturbing, in short, this disturbing strangeness which is embodied in a feminine sacred23 .

If the phenomenon of witchcraft is most often associated with women, it is perhaps because the image of the witch leaning over her pot or riding her broom is deeply rooted in the Western mentality.

Oral investigations into witchcraft, however, indicate that women did not always play a dominant role in this domain. For example, in Catherine Jolicœur’s book Les plus belles légendes acadiennes, the chapter on witchcraft in southeastern New Brunswick contains eleven stories, eight of which involve men and only three women. The author provides little additional information about the origins of the witches and sorcerers, other than mentioning in a few cases that they were foreigners. Another example that makes us question the association between women and witchcraft comes from the corpus analyzed by Peggy Martin in Newfoundland, where ten men and nine women were identified as practitioners of Amerindian witchcraft. Martin points out, however, that in the stories about witchcraft among Anglo-Terreneuvians, it is women who predominate.

If we ignore the Aboriginal groups in the Atlantic provinces, field research indicates that a greater number of English-speaking women than men have been associated with witchcraft, unlike what was the case among French-speaking people. One may wonder whether the English connotation of the term witch has something to do with this.

While in French the term sorcier/sorcière applies equally to both sexes, women are immediately thought of when the subject of witchcraft and witches is discussed. On the other hand, Helen Creighton wrote that the term witch applied without distinction to both men and women in Nova Scotian folklore . 25 She nevertheless collected much more

- Denise Lamontagne, “For a transversal approach to common knowledge in Acadia: the taoueille, Saint Anne and the witch”, Rabaska, vol. 3, 2005, p. 31-48.

- Ibid.,p. 38.

- Peggy Martin, op.cit.,p. 41.

- Helen Creighton, op.cit.,p. 18.

stories about women, if we are to judge from his publications. In Folklore of LunenburgCounty, Nova Scotia , for example, the chapter on witchcraft and the supernatural contains twenty-one stories about witches and only five about male sorcerers. 26 Creighton’s most important work on the supernatural, Bluenose Magic, contains about eighty stories of witchcraft associated with women and only twenty involving men. Jenkins notes that a similar situation exists in Irish folklore and explains this by the fact that the spells cast most often caused a shortage of milk or a malfunctioning butter churn. Spells were thus closely associated with traditional female spheres of activity. 27

In an article on the use of violence to combat witches in Newfoundland, Rieti notes that it was almost always men who used magic to harm women who were considered witches. 28 In contrast, she notes that witches do not appear to be the targets of physical attacks.

Rieti found only one case in which a white woman attacked a Mi’kmaq woman who was believed to be a witch. In this particular case, the Mi’kmaq woman’s low social status would have made her vulnerable to the actions of whites in general, regardless of gender. 29

Barbara Rieti’s thesis linking witchcraft with low social status is difficult to accept. One need only consult her work on witchcraft in Newfoundland, where an entire chapter is devoted to stories involving Jersey merchants who once played an important economic role in several regions of the island. 30 Similarly, Acadian folklore in Cape Breton abounds with stories about Jersey merchants who magically flew to the Channel Islands. 31 It is also said on Île Madame that a ship captain named Pierre Forest made a pact with the devil that allowed him to benefit from favorable winds during his trading voyages between Cape Breton and New England. 32 Merchants and ship captains could therefore practice witchcraft just

as much as beggars and other marginalized people.

Rieti is not alone in believing that social status is among the factors that lead to an individual being perceived as a witch. In Witches and

- Helen Creighton, FolkloreofLunenburgCounty,NovaScotia, Ottawa, National Museum of Canada, Bulletin no . 117, 1950, p. 46-57.

- Richard P. Jenkins, op.cit.,p. 326.

- Barbara Rieti, “Riddling the Witch:Violence against Women in Newfoundland Witch Tradition,” in Pauline Greenhill and Diane Tye (eds.), UndisciplinedWomen–TraditionandCultureinCanada,Montreal & Kingston, McGill- Queen’s University Press, 1997 , p. 28-38.

- Ibid.,pp. 80-83.

- Barbara Rieti, op. cit.,p. 54-62.

- Anselme Chiasson, op. cit.,p. 258-260.

- CÉAAC, archives of ethnology and folklore, Ronald Labelle collection, no. 1594 (1983).

Neighbours, Robin Briggs concludes that people suspected of being witches are reduced to begging and therefore dependent on the charity of their neighbours. Those who refuse to help them feel guilty and project their feelings onto those in need, leading to suspicions of witchcraft as soon as misfortune occurs. 33 The witch may therefore be a resident of the community, known to all. On the other hand, he occupies a position of inferiority because of his material poverty.

The generalizations made by scholars about the social status of witches and sorcerers are explained by the fact that the majority of witchcraft stories feature destitute people seeking material assistance. It is possible that in some places women were more likely to be destitute, hence their greater presence in witchcraft legends. Conversely, we have cited cases of male sorcerers who were part of the local elite, but no examples of a witch of high social status have been found in the Atlantic provinces. This may explain why, at least in English-speaking regions, witches are more vulnerable to attack than are male sorcerers in general.

Helen Creighton’s research echoes Barbara Rieti’s, presenting alleged witches as vulnerable to male aggression. In Bluenose Magic, there are two references to a man described as a witchmaster. According to one informant, he was called the Father of Witches because he could exercise control over witches who abused their power. 34 Thus, there

was a traditional hierarchy in Nova Scotia where a witchmaster could exercise authority over

women. In cases where the witchmaster ‘s intervention resulted in the death of a witch, Creighton’s informants in Lunenburg cited the biblical passage from Exodus 22:18: ” Thou shalt not suffer a witch to live .” 35 Similarly, some Newfoundland informants from Rieti referred to the Old Testament to justify the deaths of witches who were victims of magical practices intended to counter their spells.36

The importance given to the Bible among Protestant groups in the Maritimes and

Newfoundland may explain the traditional image of the witch as a wicked woman. In Acadian communities, suspicions of witchcraft were not directed more toward women than toward men. Catholics have not traditionally

- Robin Briggs, op. cit., p. 240.

- Helen Creighton, BluenoseMagic, op.cit., p. 21, 34-35.

- Ibid., p. 25.

- Barbara Rieti, “Riddling the Witch,” op. cit., p. 78.

based their actions on a literal interpretation of the Bible. In the Jerusalem Bible, the most widely used French version, the passage from Exodus quoted above reads: “You shall not

leave the sorceress alive.” However, none of Catherine Jolicœur’s informants cited the Bible when commenting on the witchcraft. It is striking to note that throughout the Jolicœur

collection, witchcraft does not appear as a phenomenon linked to femininity, contrary to what English-speaking researchers have observed.

Here we find a divergence between witchcraft as perceived in Acadia and in the English- speaking communities of the Atlantic provinces.

Belief in magical means to counteract spells existed in Newfoundland, as in the Maritimes, but it is difficult to determine whether these actions were more often carried out against women. The concept of the witchmaster does not appear to exist in Newfoundland folklore, but there are magical beliefs of European origin, such as the practice of making a sorcerer or witch bleed to prevent them from exercising their powers, or the practice of countering a spell by piercing an image representing the person responsible. 37 One rather unusual case involved an act of kindness in reparation for a wrong committed. For example, a merchant suffered an accident after refusing to do business with a Micmac. Rather than seeking revenge, he followed the advice given to him, which was to prepare a large meal and invite the neighbouring Indians. His wound was subsequently healed. 38 This can be paralleled by the belief that the fire that ravaged the town of Campbellton in New Brunswick in 1910 spared only one house, that of a Scottish merchant who had acted kindly towards the Micmacs.

Research in the English-speaking world suggests that men can perform positive magic to counter the effects of spells, while women only practice black magic. In Acadian folklore, however, the picture is not as clear. The CÉAAC ethnology and folklore archives contain eight examples of disenchantment following spells cast by Amerindians. In only four cases is a spell cast by a woman countered by the actions of a man. There are also two cases where two men confront each other, another where it is two women and a final story tells how a woman succeeds in countering a spell cast by a man.

In this example from northeastern New Brunswick, a Native American takes revenge on a miller who has upset him, telling him, “You don’t

- Memorial University of Newfoundland Folklore and Language Archive [now MUNFLA], Folklore Survey Cards, 6-6I, 122; MS68-10F/2-3.

- MUNFLA, Folklore Survey Cards, 68-7J, 156.

- Barbara Rieti, op.cit.,p. 49.

don’t want to grind my wheat, you won’t grind other people’s40 .” A white woman comes to the mill and says to the miller: “I know he gave you a spell. I know the Savage’s trick . I’m going to make him come back.” The woman goes home where she makes a human figure out of dough, to insert needles into. The Native American, who then suffers acute pain, suspects a magical action intended for him and quickly goes to the mill, where he says to the miller: “There is something you don’t understand in your mill. I’m going to make a round all around.” As soon as he walks around the mill, the problem disappears. We notice here that the sorcerer is Native American, while the woman who opposes him is white. She would therefore have a higher status than him in local society.

In a rare example from Acadian folklore, a spell cast by a Native American woman is magically reversed by a priest. A girl who had been making fun of three Native American women loses the use of her legs and is cured after the priest asks her parents to heat needles on the stove. 41 In this case, the priest is recommending a traditional magical practice that has no connection with the Catholic religion. The priest was commonly called upon to help people believed to be possessed or under the influence of the devil, but he was rarely consulted in cases of Native American witchcraft.

Another Acadian account, this one from Prince Edward Island, shows that the intervention of the priest was not necessarily enough to counter a spell. 42 Around the beginning of the 20th century, a couple had used their dogs to chase away a group of itinerant Micmacs. As they were leaving, the Micmacs turned around and one of them said to them: “You will bark, too.” Shortly after, the woman gave birth to a daughter who only barked like a dog. When she was older, she was taken to see an old priest who was considered a saint. The priest placed his hands on the girl’s head and read prayers, after which he told the parents: “I can assure you that she will never bark in church.” In this story, the priest fails to completely rid the girl of the spell that afflicts her, which demonstrates the extent to which the Acadians placed faith in Native American witchcraft.

A story collected in New Brunswick by Catherine Jolicœur presents a direct confrontation between Amerindian witchcraft and divine power. 43 It is said that an Acadian was visited

by an Amerindian who taught him a magic Micmac word, telling him: “If you say this word, you can

- CÉAAC, archives of ethnology and folklore, Berthe Ferron collection, no. 82 (1980).

- CÉAAC, archives of ethnology and folklore, Catherine Jolicœur collection 42. CÉAAC, , no. 13 364 (1977). archives of ethnology and folklore, Eileen Pendergast collection, no . 7 (1989).

- CÉAAC, archives of ethnology and folklore, Catherine Jolicœur collection, no. 8521 (1976).

“to kill an animal or anything.” He later tried the experiment three times, causing the death of three chickens simply by pointing at them while whispering the magic word. So he went to the priest, who made him recite prayers on his knees and placed a Bible on his head.

The priest then said to him, “Go away; you will not remember it.” A few days later, the man realized that he had completely forgotten the magic word.

The itinerant Micmacs were considered foreigners by both Acadians and Anglo-Protestants and were subject to taboos.

Despite the fact that Acadians and Micmacs practiced the same faith, Catholic priests tried to maintain a separation between the two groups. In Chezzetcook, Nova Scotia, for example, where a Micmac community existed very close to an Acadian village, the priests who served both groups did not allow the Acadians to attend the weddings of the Amerindians, or their other celebrations. This prevented the two communities from coming together.

The folkloric image of the Micmac contrasts with the idealized portrait that writers have painted of the Native American as an ally of the Acadians. In his essay Le Paysappelait Acadie, Robert Pichette devotes an entire chapter to the “myth of the noble savage .” 44 He explains that the Acadians showed the deepest contempt for the Native Americans for most of their history, even though the latter fought alongside them against the British. The romantic image of a lasting friendship between the two groups was supposedly created by Acadian authors of the past. Denis Bourque states that from the 17th century to the mid- 20th century , authors consistently expressed their admiration for the Natives, believing that

they deserved to be recognized not only as allies and friends, but also as the s,aviors of the

Acadian people during the post-deportation period. 45 Bourque notes, however, that the authors still preferred to maintain a distance between the two peoples, specifying that two of the most important writers of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Pascal Poirier and André-Thaddée Bourque, both insisted on the fact that no “Indian blood” flowed in the veins of the Acadian people. André-Thaddée Bourque even went so far as to declare that “among the Acadians of the Maritime provinces, there are very few […] if any at all, who have in their veins blood other than that which their ancestors brought them from old France .” 46

- Robert Pichette, TheCountryCalledAcadia,Moncton, Éditions d’Acadie, 2006, pp. 215-240.

- Denis Bourque, “Images of the Amerindian in Acadian Literature (1609-1956)”, PortAcadie,nos. 6-7, 2004-2005, p. 216-217.

- Ibid.,p. 209.

In Acadian society in the past, mixed marriages with Amerindians were frowned upon. The case of Marie Comeau, nicknamed “La Mariecomo,” provides a good example. Although she lived from 1838 to 1910, her legend has remained alive. In the preface to his novel based on this controversial character, Régis Brun writes that Mariecomo had caused great unease among the Acadian population of southeastern New Brunswick because she had married a Micmac and then gone to live among his people . 47 She was generally feared, but some also admired her. The testimonies collected about her often tell that she had been seduced by a Micmac sorcerer and that she herself became a witch, but there were those who believed that she had simply married for love: “She had fallen in love with this savage, then she had married him. Well, they always said – her parents, there – that he had bewitched her48 .”

Several oral stories convey the belief that Acadian women who fell in love with a Micmac were necessarily victims of spells.

One version tells how the brother and sister of a girl who was madly in love with a young Micmac told another Native American, who explained to them how to check if she was the victim of a spell. He told them to look inside their sister’s shoes to see if there was a leaf hidden in the sole and then to remove the leaf, which they did that same evening.

The girl then apparently stopped being attracted to the Micmac.

Other stories tell of an offended Micmac lover taking revenge by casting a spell on the girl he was courting. In one case, a young Acadian woman suffered seizures after being bewitched by a Micmac whom her mother had banished from their home. After a few days, an old man went to the scene and inquired about the physical appearance of the person responsible. He then drew the Micmac’s face on a sheet of paper and pricked it with a fork. The rejected lover then showed up with sores on his face and shouted “Stop!” after which he removed the spell. 50 Such stories would no doubt have served as warnings to young girls who might have been attracted to Micmacs.

One of the oldest stories dealing with Native American witchcraft in Acadia concerns interracial love affairs. This story focuses on Joseph Gueguen (1741-1825), an important figure in the post-deportation period in southeastern New Brunswick, where his many descendants

47. Régis Brun, LaMariecomo,Moncton, Éd. Perce-Neige, 2006 (new revised and corrected edition), p. 3-4.

- CÉAAC, archives of ethnology and folklore, Lauraine Léger collection, no. 463 (1969) and no. 1240 (1977); Catherine Jolicoeur collection, no. 10 034 (1976).

- CÉAAC, archives of ethnology and folklore, Catherine Jolicœur collection, no. 6 260 (1976).

- CÉAAC, archives of ethnology and folklore, Catherine Jolicœur collection, no. 7 863 (1976).

bear the surname “Goguen.” In 1771, Gueguen, a widower with four young children, married a widow named Marie Quessy. The couple separated seven years later, after a long period of conflict. According to oral tradition, Marie Quessy had been bewitched by a Micmac woman whom she had abruptly chased away because she could no longer bear to be approached by Amerindian beggars, either at home or in the business she ran with her husband. 51 Tradition tells that she had been the victim of a spell characterized by extreme jealousy felt towards her husband, whom she accused of infidelity with Micmac women.

This story was part of the collective memory of the Acadians of New Brunswick for over a hundred years, until Placide Gaudet put it into writing at the end of the 19th century. 52 To understand the fact, it is important to know that the separation of the Gueguen/Quessy couple had caused a real scandal at the time, especially since Joseph Gueguen had tried to obtain a divorce more than once. But to understand how the legend of the bewitchment of Marie Quessy was born, it is useful to examine the situation in which this couple lived. Joseph Gueguen had studied at the Séminaire de Québec during his youth, and then served as personal secretary to a missionary who worked among the Micmacs of the Miramichi region. Gueguen spoke Micmac fluently and even

wrote in this language. 53 Amerindians passing through Cocagne could easily have chosen to stop at his home, sure to meet a friend there.

Marie Quessy, on the other hand, was certainly not on such good terms with the Micmacs, which would have caused conflict with her husband. Given the prejudices that the Acadians felt toward the Micmacs in general, Marie’s accusations of infidelity toward her husband must have caused unease among the population, given Joseph Gueguen’s status as a leading member of the local elite. In such a case, it would be natural to seek a supernatural explanation for a distressing situation.

In Newfoundland folklore, as in Acadia, witchcraft legends centered on Native women most often tell the story of a Mi’kmaq woman who casts a spell on whites who refuse to buy her products or who refuse her food. There is, however, one particular legend that relates to the annual migration of the Mi’kmaq between Cape Breton and southern Newfoundland. The most widespread version describes how baskets belonging to a Mi’kmaq woman were damaged during the William

Carson’scrossing from Nova Scotia to Newfoundland in the early 1960s. Despite the

- Régis Brun, PioneerofthenewAcadia,Moncton, Éditions d’Acadie, 1984, p. 52-53.

- CÉAAC, private archives, Placide-Gaudet funds, 1.100.7, “About Joseph Gueguen”.

- Régis Brun, PioneerofthenewAcadia,op.cit.,p. 66-67.

The woman’s claims were met with refusal by Canadian National to compensate her for her losses. She informed ferry officials that they would suffer losses before the end of the year, and shortly thereafter several Canadian National ships were reported to have run aground. 54 As for the William Carson itself, this large ferry mysteriously sank off the coast of Newfoundland in 1977. 55

Witchcraft stories involving Mi’kmaq men in Newfoundland vary considerably, but most

often relate to clashes between hunters and white traders. Mi’kmaq hunters cast spells on traders who refused to buy their pelts, or who offered them unacceptable prices. In one

example from the village of Gaultois, a trader offered low prices to two hunters, explaining that their pelts were worth little because of their inferior colour. The Mi’kmaq then cast a spell on him, rendering him colour blind. 56 Rieti has identified several versions of this story from the south coast of Newfoundland. 57 The vulnerable position of the Micmac hunters with regard to the traders is similar to that of Newfoundland fishermen and hunters in general, which may explain why the legend is so widespread in regional folklore: white people who had also been victims of injustice at the hands of the traders probably enjoyed listening to stories of how revenge had already been taken on them.

From the collections held in the Memorial University Folklore Archives, it is apparent that rural Newfoundlanders were generally in a similar socio-economic situation to the Mi’kmaq, and that there may have been competition between whites and Indians over employment. There are, for example, stories of a Mi’kmaq man working alongside whites on a deep-sea fishing boat casting a curse on the captain and crew after he was laid off. 58 There is at least one story in Newfoundland about a man being cursed after refusing shelter to a Mi’kmaq couple, but the reverse situation also occurs, where a white hunter is housed and fed by an Indian woman who casts a curse on him after he leaves his home without sharing with her the partridges he brought home . 59 In the latter case, it is the white man who is the object of the generosity of the Micmacs, another indication that social status does not necessarily have anything to do with the perception that an individual is perhaps a sorcerer.

- MUNFLA, Folklore Survey Cards, 68-17K/84.

- Barbara Rieti, op.cit.,p. 54.

- MUNFLA, Folklore Survey Cards, 68-3K, 156; 69-6I, 117.

- Barbara Rieti, op.cit.,p. 47.

- MUNFLA, Folklore Survey Cards, 68-7J, 158.

- MUNFLA, MB68-13D/8-11; MS68-10F.

In Newfoundland, as in Acadia, it seems that the distrust that existed towards outsiders was the main catalyst for witchcraft stories. Rieti notes that in Labrador, there are no witchcraft stories involving Aboriginal people, whether Innu or Inuit. She suggests that these groups may not have experienced the same tensions in their relations with whites, given the less frequent nature of their contact with them. 60 In Labrador, whites would therefore have felt less threatened by the proximity of Aboriginal people.

Archival sources indicate that there are more accounts of clashes between whites and Mi’kmaq in Acadia than in Newfoundland, which is not surprising given that Aboriginal people were much more numerous in the Maritimes. Although Acadians often lived in close proximity to the Mi’kmaq, various strategies were used to prevent any social and cultural rapprochement with them. From early childhood, young Acadians were taught that the “Savages” were dangerous. Parents told their children that the “Savages” would come for them if they did not behave. 61 When babies were born, children were sent to the neighbours with the message that the “Savages” were coming with a baby. When the children saw their mother bedridden

upon their return, it was explained that the “Savages” had broken her leg when they left.62 However, it did happen that the barrier erected by prejudice was crossed to create friendly ties with the Amerindians.

A Moncton woman, for example, recounts that one day a Mi’kmaq woman stopped by her house to ask for tea. She immediately gave her a bag containing her entire supply of tea in order to keep her away, so afraid was she that the Amerindian woman would take her children away. Several years after the incident, this same Acadian woman became friends with a Mi’kmaq woman who went to the market in Moncton every Saturday: “It was just as if she had been my sister. I loved her just as much .” 63

The following example demonstrates how Acadians could be haunted by feelings that combined fear, dread, and guilt toward Aboriginal people. In my doctoral thesis,64 I explain how Allain (or Allan) Kelly, an Acadian from New Brunswick of part Irish and Scottish descent, suffered for over twenty years from a serious infection that affected his left foot, eventually having it amputated.

- Barbara Rieti, op. cit.,p. 54.

- CÉAAC, archives of ethnology and folklore, Catherine Jolicœur collection, no. 12 596 (1977).

- CÉAAC, archives of ethnology and folklore, Gratien Bossé collection, no. 97 (1978).

- CÉAAC, archives of ethnology and folklore, Lauraine Léger collection, no. 893 (1977).

- Ronald Labelle, “I Had Power from Above: The Representation of Identity in Testimony autobiographical work of Allain Kelly”, Thesis (Ph.D.), Université Laval, 2001, p. 83-84.

partial foot injury at the Campbellton hospital. The infection had developed as a child, shortly after he kicked the straw hat of a young Mi’kmaq girl walking along the shore with her mother, and a gust of wind blew the hat away. Kelly always feared the infection was the result of a spell cast by the girl’s mother. Twenty years later, when he woke up after the amputation, the same woman appeared at the entrance to his hospital room, repeating, ” They cut the foot!”

Theycutthefoot!»(They cut off his foot). Then she disappeared.

We have seen that great barriers have always been erected between the Micmacs and the whites in the Atlantic provinces, whether they were Acadians, Anglophones from the Maritimes or Newfoundland. Through acts of mutual aid and fraternity, it was nevertheless possible in rare cases to overcome the suspicions that were deeply rooted in the culture of the whites. An incident that took place in northeastern New Brunswick during the 1940s provides us with an example, when two Aboriginal families asked an Acadian woman if

they could camp on her family land while they cut ash trees in a nearby forest. When she agreed, the Micmacs told her that several neighbours had refused to allow them to stop at their home. As they left, they gave their host family as a token of their gratitude an ash sewing basket, an axe handle and a wooden toy. 65

In 2004, during the World Acadian Congress which marked the 400th anniversary of the founding of Acadia, the Société nationale de l’Acadie symbolically presented the Léger- Comeau Medal to the Micmac people in thanks for the help offered to the Acadians throughout their history.

For such a gesture to have any real meaning, the Acadians would have to recognize the racist attitude that marked their contacts with the Micmacs throughout history. Such a gesture is not for tomorrow, although the perception of the Aboriginals is gradually improving in Acadia. It will also take a long time before prejudices against the Aboriginals disappear among the anglophones of the Maritimes and among the Newfoundlanders. After having considered the Micmacs as potentially dangerous foreigners for entire centuries, the Whites will have to put a lot of effort into building a new vision of their neighbours.

Finally, by comparing the folklore of the Acadians and that of the Anglo-Terreneuvians, I have tried here to go beyond the generalizations that are too often made about witchcraft. We have seen that accusations of witchcraft were far from being limited to women. We cannot therefore simply consider the belief in witchcraft as being the reflection of a

- CÉAAC, archives of ethnology and folklore, Catherine Jolicœur collection, no. 12 416 (1977).

fear of mysterious feminine powers. Furthermore, the omnipresent fear of “others” or foreigners in general may well explain the large number of witchcraft stories that exist throughout the Atlantic provinces. Anglophones, Francophones, Catholics and Protestants: all shared the same racial prejudices and the same mentality mixing Christian faith and superstition. In this context, the Micmacs, because of their culture and way of life different from those of the whites, were perfectly placed to be perceived as witches.